城市中心公园的典范:纽约中央公园

纽约中央公园(Central Park)是美国景观设计之父奥姆斯特德(Frederick Law Olmsted)与风景园林设计师沃克斯(Calbert Vaux)共同设计建造的公园,号称“纽约后花园”。它的意义不仅在于它是全世界最著名的城市公园,还在于在其规划建设中,诞生了一个新的学科——景观设计学(Landscape Architecture)。

在曼哈顿岛的中心有一大片雕塑般的自然景观。这片大片绿地 – 中央公园 – 是新城市愿景的第一个伟大宣言,旨在将自然引入美国商业和工业城市的中心。作为其巨大成功的一个衡量标准,该公园迅速而持久地成为纽约市最受欢迎的公共景点之一,而大都市的标志往往因其商业力量而非艺术而闻名。

In the center of Manhattan Island lies a great expanse of sculpted nature. This large swath of greenery—Central Park—was the first great manifesto of a new urban vision that sought to introduce nature into the heart of commercial and industrial cities in the United States. As a measure of its tremendous success, the park quickly and enduringly became one of the most popular public attractions in New York City and an icon of a metropolis often famed more for its commercial power than for its art.

自然与城市

中央公园的规模和区别的设计必然是偶然的历史条件的产物。首先,从广义上讲,这个公园是美国人对自然景观的迷恋的一种表现。自殖民时代以来,自然景观一直是美国民族性格的特征。虽然人们普遍认为商业城市一直是必要的,但十九世纪的美国艺术,文学,政治和大众文化都将农村土地作为国家“例外主义”的核心要素而庆祝。亨利·戴维·梭罗,其著作《瓦尔登》(1854年)记录了他在马萨诸塞州农村寻求自我复兴的过程。他建议每个美国的城市都应该为“原始森林”留出土地,以“保存在乡村生活的所有好处”。

A design of the magnitude and distinction of Central Park is necessarily the product of a fortuitous set of historical conditions. First, and broadly speaking, the park is an expression of the American fascination with the natural landscape that had defined the national character since colonial times. Although it was widely recognized that commercial cities had always been necessary, nineteenth-century American art, literature, politics, and popular culture all celebrated rural land as a central element of the nation’s “exceptionalism.” Henry David Thoreau, whose book Walden (1854) chronicled his retreat for self-renewal in rural Massachusetts, suggested every American city should be obliged to set aside land for a “primitive forest” in order to “preserve all the advantages of living in the country.”

到19世纪中叶,第二个关键因素是人们普遍认识到工业城市需要精心规划。诗人和报纸编辑、旅游作家威廉·卡伦·布莱恩特和园艺师、中央公园的设计者,弗雷德里克·劳·奥姆斯特德等改革者拥抱着城市的未来,但他们希望通过引入大自然,以作为对他们所看到的大城市不安全和不卫生的品质的解毒剂,来改善所有城市居民的生活。当然,这些改革者们知道,真正的纯朴自然在城市中心是不可能的。相反,他们试图培育一种人造的田园景观,通过人类的发明和设计,捕捉大自然的最佳品质。大公园将成为城市的肺部。改革家们宣称自己有一种浪漫的信念,即置身于大自然之中,可以缓解神经和心理,有助于“解开”某些生理和心理上的紧张关系。

The second crucial factor, by the middle of the nineteenth century, was the widespread awareness that industrial cities needed to be carefully planned. Reformers such as the poet and newspaper editor William Cullen Bryant and the travel writer, horticulturalist, and co-designer of Central Park, Frederick Law Olmsted embraced the urban future, but they wanted to better the lives of all city dwellers by introducing nature as an antidote to what they saw as the unsafe and unsanitary qualities of large cities. Of course, these reformers knew that true rustic nature was impossible in the middle of cities. Instead, they sought to cultivate a man-made, pastoral landscape that captured the best qualities of nature as filtered through human invention and design. Large parks were to be “the lungs of the city.” The reformers professed a Romantic conviction that being surrounded by nature assuaged the nerves and mind and helped “unbend” certain physical and psychological tensions.

然而,一些改革者以更加家长式的方式表达了他们的观点,表现出对穷人和工人阶级的蔑视。他们认为,中央公园的田园风光应该成为改善粗俗无礼行为的场所,尤其是那些当时在纽约这样的大城市里发现的新移民,这些移民通常都很贫穷。奥姆斯特德自己写道,“纽约大部分人都对公园的社会目的一无所知”,需要“接受正确使用它的培训”。奥姆斯特德的最初目的是引导游客在中央公园漫步并静静地欣赏自然风光; 他们不像今天那样,在剧烈运动、大型节日或音乐会,或任何其他会扰乱公园田园风光的行为中参加。早些时候,他和他的设计伙伴卡尔弗特·沃克斯(Calvert Vaux)颁布了规定,以达到公园游客所期望的行为:礼貌的社交能力,然后可能渗入城市本身的行为。

Some reformers, though, expressed their views in a more paternalistic manner, showing disdain toward the poor and working classes. They argued that Central Park’s bucolic scenery should serve as a setting to refine the coarse, impolite manners thought to characterize especially the new, often impoverished immigrants then found in large cities like New York. Olmsted himself wrote that “a large part of the people of New York are ignorant” of a park’s social purpose and needed “to be trained in the proper use of it.” Olmsted’s original objective was to direct visitors to stroll through Central Park and quietly admire the natural scenery; they were not to partake, as they often do today, in strenuous exercise, large festivals or concerts, or any other behavior that would disturb the park’s bucolic ambience. Early on, he and his design partner Calvert Vaux issued regulations to achieve the desired behavior among park visitors: a polite sociability that might then filter out into behavior in the city itself.

英国风景

这些社会问题依赖于英格兰早期开创的自然景观的美学。18世纪的英国园林,以及19世纪早期巴黎郊区的墓园,特别是Père-Lachaise,对美国的景观设计产生了强烈的影响。例如,在19世纪30年代,乡村公墓运动产生了重要的景观设计,包括马萨诸塞州剑桥的奥本山、布鲁克林的格林伍德(下图)和费城的劳雷尔山。这些郊区墓地旨在为游客提供一个安静的休憩场所,并为他们提供身心健康方面的好处。它们是根据英国风景园林(上图)的美学设计的,其中蜿蜒的小路,开阔的草地,池塘和偶尔的建筑“愚蠢”创造了风景如画的效果,这不同于严格对称或几何布局的意大利和法国园林的传统,如佛罗伦萨Boboli花园或在凡尔赛宫皇家花园。

These social concerns relied on the aesthetics of the natural landscape pioneered earlier in England. The “English landscape gardens” of the eighteenth century, as well as

the early nineteenth-century suburban cemeteries of Paris, especially Père-Lachaise, strongly influenced landscape design in the United States. In the 1830s, for example, the Rural Cemetery Movement produced important landscape designs including Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Green-Wood in Brooklyn (below), and Laurel Hill in Philadelphia. These suburban cemeteries were intended to provide a quiet retreat and confer physical and mental health benefits on visitors. They were designed according to the aesthetics of the English landscape garden (above), in which winding paths, open meadows, ponds, and occasional architectural “follies” created picturesque effects very different from the rigidly symmetrical or geometrical layouts of gardens in the Italian and French traditions, such as the Boboli Gardens in Florence or the royal gardens at Versailles.

政治与中央公园

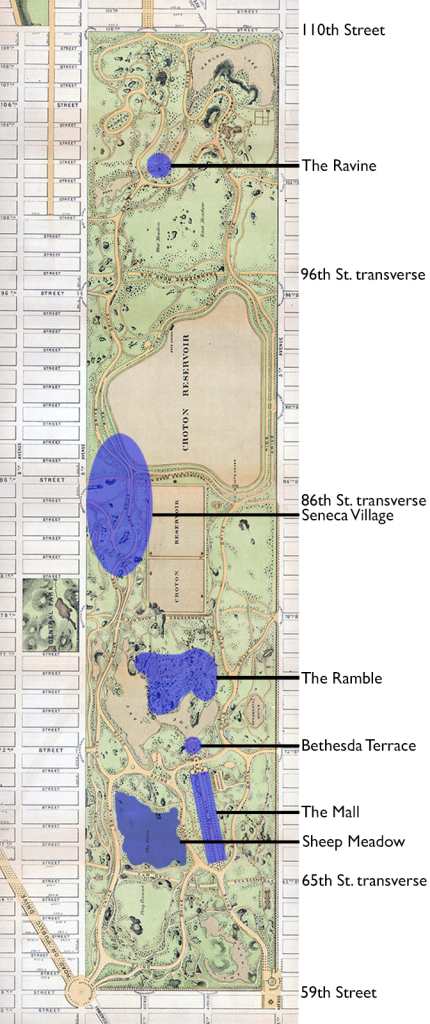

政治支持是中央公园发展的第三个主要因素。为该公园获得的土地已被纳入该市1811年的网格化城市规划,这是早期控制曼哈顿岛发展的努力。这个地区没有树木,多岩石。在西侧,1855年的人口普查中有264名居民。众所周知,“塞内卡村”(Seneca Village)中约有一半的房子是由自由的非洲裔美国人以及许多德国和爱尔兰移民所拥有的。那里至少有两座教堂、墓地和一所学校。市政府和州政府利用土地征用权的法律权利将土地作为中央公园的一部分,在1857年强制驱逐所有居民。

Political support was the third major factor in Central Park’s development. The land acquired for the park had been included in the city’s gridded urban plan of 1811, which was an early effort to take control of Manhattan Island’s development. The area was treeless, rocky terrain. On the west side it encompassed a small settlement that counted 264 residents in the 1855 census. About half of the modest houses in “Seneca Village,” as it was known, were owned by free African Americans, along with many German and Irish immigrants. There were at least two churches, cemeteries, and a school. City and state government used the legal power of eminent domain to claim the land as part of Central Park, forcibly evicting all the residents by 1857.

1856年,纽约工程师埃格伯特·维勒(Egbert Viele)负责中央公园的第一个未建成的规划。由于对曼哈顿未来发展的预测把建房地的边界推得越来越远,因此不健康和不雅观的土地是改革的好地方。改革家和政客们也很快意识到1811年的计划没有充分考虑到娱乐和其他类型的开放空间的需要。即使是这个计划提供的几个公园,在过去的几十年里也大多是建立在房地产利益凌驾于公共利益之上的。

New York engineer Egbert Viele—who was responsible for the first, unbuilt plan for Central Park in 1856—described the land as a “pestilential spot” with “miasmatic odors” emanating from the untended ground. Unhealthy and unsightly, the land was ripe for reform as projections for Manhattan’s future growth pushed the boundary of built-up land further and further north. Reformers and politicians also soon realized that the 1811 plan had not sufficiently taken account of the need for recreational and other types of open space. Even the few parks provided by that plan had mostly been built over in the intervening decades as real estate interests trumped the public good.

1853年,在布莱恩特(Bryant)、景观设计师安德鲁•杰克逊•唐宁(Andrew Jackson Downing)等人的鼓动下,纽约州批准在曼哈顿建造一座大型公园,最初由维勒(Viele)建造和设计。然而,他的设计被认为是敷衍了事,缺乏艺术性或独创性。中央公园委员会,也就是政府机构,任命弗雷德里克·劳·奥姆斯特德为工程总监,并呼吁公开竞争新的设计。

In 1853, after more than a decade of agitation by Bryant, landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing, and others, the state of New York authorized the creation of a large park in Manhattan, originally to be built and designed by Viele. However, his design was considered perfunctory, offering little in the way of artistry or ingenuity. The Central Park Commissioners, as the governmental body was known, appointed Frederick Law Olmsted as superintendent of works and called for an open competition for a new design.

奥姆斯特德不是设计师或工程师。在北欧,墨西哥和其他地方旅行之前,他曾在史坦顿岛担任农民和园艺爱好者多年。他的旅行激励他开始写作,后来又出版了杂志。Calvert Vaux向奥姆斯特德询问是否共同向公园竞赛提交设计。Vaux是一位英国建筑师,之前曾与唐宁合作,并热切地接受了后者关于景观的浪漫主义思想。他与奥姆斯特德的合作导致了一群志同道合,意志坚定的人,他们决心将公园塑造成他们共同的愿景。

Olmsted was not a designer or engineer. He had been a farmer and horticultural enthusiast on Staten Island for several years before traveling in northern Europe, Mexico, and elsewhere. His travels inspired him to take up writing and, later, magazine publishing. Calvert Vaux approached Olmsted about jointly submitting a design to the park competition. Vaux, an English architect, had earlier worked in partnership with Downing and eagerly took up the latter’s Romantic ideas about landscape. His partnership with Olmsted resulted in a pairing of like-minded, strong-willed individuals determined to mold the park to their shared vision.

设计

奥姆斯特德和沃克斯凭借他们的“Greensward Plan”赢得了设计竞赛,这是提交的32个方案中的最后一个。他们用两个元素将Greensward Plan与竞争对手的设计区分开来:一个是他们的景观特征的纯粹诱惑,在他们的提交中包括12个前后面板。另一个是行人和越野车(现为车辆)交通的巧妙分离。

Olmsted and Vaux won the design competition with their “Greensward Plan,” the last of thirty-two to be submitted. Two elements distinguished the Greensward design from those of their competitors. One was the sheer allure of their landscape features, conveyed in twelve before-and-after panels included in their submission. The other was the ingenious separation of pedestrian and cross-park carriage (now vehicular) traffic.

竞赛简讯要求,四条道路应通过公园连接曼哈顿的东西两侧。所有其他参赛作品都将这些道路铺在地面上,有效地将公园划分为五个区域,由街道交通隔开。然而,奥姆斯特德和沃克斯将他们的“横向”道路埋在地下水位之下,并创造了一个由设计地形区分的连续广阔的公园。正如他们在施工期间发现的那样,这一关键发明使他们有机会增加公园风景如画的风景,因为横跨横梁和新娘路径的许多车道和行走路径都可以通过迷人的桥梁进行装饰。

The competition brief had insisted that four roadways should connect the east and west sides of Manhattan through the park. All other submissions put those roads on the ground surface, effectively dividing the park into five zones separated by street traffic. However, Olmsted and Vaux submerged their transverse roads below ground level and created a continuous expanse of park differentiated by designed topography. As they discovered during construction, this critical invention gave them the chance to increase the park s picturesque scenery since the many drives and walking paths that cross over the transverses and bridal paths could be embellished by attractive bridges.

从南到北,公园的布局是为了创造独特的视觉体验,帮助游客在广阔的空间中遨游,创造出与周围网格城市的直线形成强烈对比的如画般的变化。在水库的南面——最初有三个,但今天只有最大的不规则湖——公园是一系列的牧区,包括一个叫做游行广场的大空地(现在的羊草甸),周围是矮树丛或小树林(上图)。

From south to north, the park is laid out to create distinct visual experiences, helping the visitor navigate the vast space and creating picturesque variety in strong contrast to the rectilinearity of the gridded city around it. South of the reservoirs—there were originally three but today only the largest irregular one remains as a lake—the park is a series of pastoral areas, including the large glade called the Parade Ground (now the Sheep Meadow) surrounded by copses or small groves of trees (above).

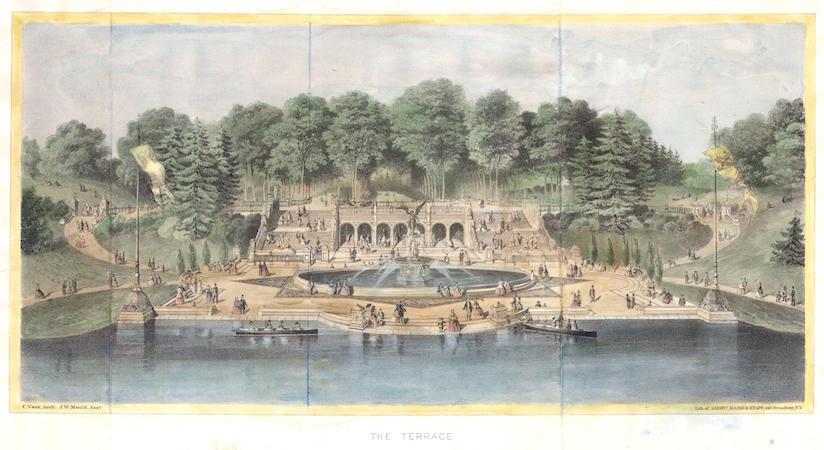

在公园的南端,我们发现了一个与自然主义分离的区域:长长的树木和长凳上的海滨长廊现在被称为购物中心(上图),通往露台和贝塞斯达喷泉(下图)。

In the southern end of the park, we find one area that departs from the naturalism: the long, tree- and bench-lined Promenade now know as the Mall (above) which leads to the Terrace and Bethesda Fountain (below).

露台分为上部和下部,非常古典的环境,宽阔,对称的楼梯和正式感。Jacob Wrey Mold是一位英国建筑师,直到1874年为Olmsted和Vaux公园工作,设计了它的装饰品。

The Terrace is divided into upper and lower sections, a remarkably classical environment with wide, symmetrical stairs and a sense of formality. Jacob Wrey Mould, an English architect who worked on the park for Olmsted and Vaux until 1874, designed its ornament.

露台是一个令人惊讶和优雅的空间,是周围景观的愉悦衬托。在喷泉的中央,是由雕刻家艾玛·斯图宾斯(Emma Stubbins)的“水天使”(Angel of the Waters)在1873年建造的。在露台阶梯之间是拱廊,这是一个长长的地下空间,拥有令人惊叹的天花板,装饰着由Mold设计并由英国Minton Tile Works制造的瓷砖。露台的正式却又欢庆的外观很适合作为城市“露天接待厅”的空间。

A surprising and elegant space, the Terrace is a delightful foil to the landscape around it. At its center is the much-photographed fountain surmounted by sculptor Emma Stubbins’ Angel of the Waters, installed in 1873 (left). Between the Terrace steps is the Arcade, a long subterranean space with a stunning ceiling decorated with tiles designed by Mould and manufactured by the Minton Tile Works in England. The formal but festive appearance of the Terrace is appropriate for a space conceived as the city’s “open air hall of reception.”

湖的北边是Ramble,沿着当地石头岩石露出的一系列小而蜿蜒的小路,被称为“schist”,可以在整个公园看到。在公园的最北端是最崎岖的景观,最茂密的树叶,然后现在是公园中游客最少的区域。但该区域提供了一些公园最令人惊叹的特色,包括带有小溪,瀑布的山沟和由巨大的粗糙石头制成的墓穴般的峡谷拱门。该区域的宁静是一种令人难以忘怀的经历;比起它与繁忙的街道之间的实际距离,它给人的感觉要隐蔽得多。

North of the Lake is the Ramble, a series of small, twisting paths along rocky outcroppings of the local stone, called schist, that can be seen throughout the park. At the northernmost edge of the park is the most rugged landscape with the densest foliage, then and now the park’s least visited section. But the area offers some of the park’s most stunning features, including the Ravine with its small brook, waterfalls, and tomb-like Glen Span Arch, made from massive, rough-faced stones. The quiet of the area is an almost haunting experience; it feels much more secluded than its actual distance from the busy surrounding streets would suggest.

公园的影响力

中央公园是其特定时刻的产物,是美国内战前十年中美学思想,城市关注和政治意愿的结合。它的迅速成功为奥姆斯特德和沃克斯带来了将他们的方法应用于景观设计的其他机会:一些重要的项目是布鲁克林的展望公园(1866 -73)、布法罗公园系统(1868年开始)和伊利诺斯州河畔的郊区(1868年)。

Central Park was very much a product of its particular moment in time, a combination of aesthetic ideas, urban concerns, and political will that coalesced in the decade before the Civil War. Its instant success led to other opportunities for Olmsted and Vaux to apply their approach to landscape design: a few of the important projects were Prospect Park in Brooklyn (1866-73), the Buffalo park system (begun 1868), and the suburb of Riverside, Illinois (1868).

后来,奥姆斯特德还开展了一项蓬勃发展的实践:他设计了斯坦福大学校区(1889年),亚特兰大德鲁伊山区(1892年),以及芝加哥世界哥伦比亚博览会(1893年)的场地 -——这只是众多项目中的三个。奥姆斯特德和沃克斯开发的景观哲学首次在中央公园展出,具有持久的影响力,鼓舞人心,例如,延斯·詹森(Jens Jensen)在芝加哥和二十世纪初的其他地方的“草原景观”。当《哈珀杂志》(Harper’s Magazine)宣称中央公园是“这个国家有史以来最精美的艺术作品”时,这并不夸张。”也许现在仍然是。

Later, working apart from Vaux, Olmsted had a flourishing practice: he designed the campus of Stanford University (1889), the Druid Hills district in Atlanta (1892), and the grounds of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893)—just three among many projects. The landscape philosophy developed by Olmsted and Vaux and first expressed at Central Park had lasting influence, inspiring, for instance, Jens Jensen’s “prairie landscapes” in Chicago and elsewhere in the early twentieth century. It was arguably no exaggeration when Harper’s Magazine declared in 1862 that Central Park was “the finest work of art ever executed in this country.” It may still be.

本文属于作者原创文章,未经允许不得转载,如有转载请联系我们或原作者(邮箱:Landarchcn@outlook.com)。